Tags

1957 Italian Grand Prix, 1958 Grand Prix Season, Colin Chapman, Ferrari, Frank Costin, John Cooper, Mike Hawthorn, Stirling Moss, Tony Brooks, Tony Vandervell, Vanwall

We shape our self to fit this world

and by the world are shaped again.

The visible and the invisible

working together in common cause,

to produce the miraculous.

I am thinking of the way the intangible air

passed at speed round a shaped wing

easily holds our weight.

So may we, in this life trust

to those elements we have yet to see

or imagine, and find the true

theireof our own self, by forming it well

to the great intangibles about us.

~Working Together – David Whyte~

Despite their position deep in enemy territory, three green aliens had captured the entire front row of the grid. Behind them, poised for attack, flowed a crimson tide of scarlet machinery. For the fanatical Tifosi, to have the front row occupied by cars clad only in the camouflage-like garb of the opposition was not just unbelievable, it was unthinkable. Swiftly reacting to the impertinence of the intruders, the grid layout was amended from the traditional 3-4-3 to 4-3-4. Squeezed onto the far end of the front row was now a splash of red…Juan Manuel Fangio and his Maserati 250F handily placed to challenge in the skirmish for the first corner.

The leader of the British squad that had invaded Italian soil was Tony Vandervell. September 8 was not only race day; it was also Vandervell’s 59th birthday. The 1957 Italian Grand Prix would continue Vanwall’s frontal advance in Formula One. Despite the euphoria-inducing front row lockout, Vandervell still had his feet planted firmly on the ground. His only interest was in winning. Securing the first three places on the grid were only the preliminaries to the final assault.

Vanwall had already unlocked their previously unrealised speed during the 1957 Grand Prix season. In July, enveloped by a force field of patriotic fervour, Stirling Moss, closing out the race in Tony Brooks’ car, had recovered from ninth place to win their home Grand Prix at Aintree…the first World Championship victory for a British born driver in a British built car.

Their second victory came a month later, Stirling Moss winning at the high-octane street circuit of Pescara, Formula One’s only championship appearance at the intimidating 25.8-kilometre track situated on the Adriatic Coast of Italy. These previous triumphs paled into insignificance compared to the possibility of conquering their antagonists at the hallowed grounds of Italy’s oldest race track…Monza.

Tony Vandervell’s aspiration may have been “to beat those bloody red cars”, but his first Grand Prix race car began its life painted red. And it was not just any red. It was Ferrari red! Needless to say, it didn’t stay that colour for long. Before appearing on the track at the 1949 British Grand Prix, the Ferrari Tipo 125 GP was reincarnated, freshly painted with British Racing Green, and embellished with the appellation of “Thinwall Special”. But beneath the name and the colour, it was all Ferrari.

With enough surplus funds to buy a Ferrari, it was apparent that Vandervell had more ready money than most. The source of his capital came from bearings…thin-wall bearings. Negating the need to dismantle the lower end of the engine to fit them saved both time and money. Tony didn’t invent them, but he was quick to see their potential. Patiently loitering for six days outside the office of Ben Hopkins, their American co-inventor, he eventually obtained the exclusive UK rights to their manufacture.

As a young man, Tony’s focus had been more on amassing speed than assets. While still a teenager, he was a regular attendee at local hill-climbs, riding a Norton motorcycle. Academia and Tony had never seen eye to eye, so lying about his age, he quit school in 1916 and joined the Army Service Corps, continuing to use his love of speed as a despatch rider. Promotion to workshop officer furthered his mechanical education, tasked with rehabilitating London buses conscripted for use as troop transport vehicles in France.

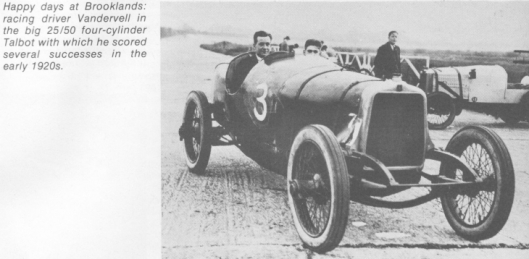

After World War One, Vandervell diversified into four wheels, buying a Talbot from Malcolm Campbell, though he also continued to race his Norton motorcycle. Autocar, reporting on his exploits at one of the local hill climbs, wrote that “G. A. Vandervell must be given credit for the most hair-raising skills. His stripped four-seater Talbot tackled the first corner at over 40 mph, skated round until it was almost broadside on the hill, slid the opposite way, when the driver cleverly corrected the steering, shot back again…and continued round the second bend at high speed, executing the same gyrations, the solitary passenger in the back bouncing from one side of the body to the other…”

Photo from Vanwall – The Story of Tony Vandervell and His Racing Cars

Vandervell Senior had made his fortune in electronics. He attached lighting equipment, initially to horse-drawn carriages, but later to vehicles powered by combustible liquids rather than green vegetation. Thankful that his son had found a more sensible outlet for his energy and talents than racing, he provided the necessary financial backing to get the fledgling factory started. Tony was now on his way to making his own substantial fortune from the smaller fortune his father had risked on him. Factory operations began in 1936, and by 1939 the onset of war had escalated demand to half a million bearings…per week!

Bearings continued to be a growth industry even after the war, so there was no shortage of superfluous funds to divert into satisfying Tony’s addiction to speed. His foray into racing post World War Two began as one of the many sponsors and supporters of BRM. Unfortunately, BRM’s progress was slow and haphazard. There were too many bosses with a plethora of ideas, but not enough doers with the pragmatism needed to bring those ideas into fruition.

Racing was not an activity based on the theoretical. It was instead an activity eminently practical. Vandervell was nothing if not practical. He decided it was too time-consuming to construct the first car from scratch, only to find out the multitude of reasons why it wasn’t fast, and probably never would be. What was needed was a proven race car. It could then teach them not only how to build a car, but just as important, how to race it.

Vandervell was after the best race car money could buy. A current Ferrari was never going to be a bargain. It involved adding 4,350 pounds to the coffers of Ferrari, as well as another 5,430 pounds into the even greedier hands of Her Majesty’s Customs and Excise, needed to gain permission to race the rare and costly import. Vandervell may have thought he was getting up to date Ferrari technology. Instead, he got the 1948 car…albeit slightly upgraded…but not surprisingly still a significant step behind that furnished to the favoured drivers of the Scuderia.

Photo: John Chapman

The original Ferrari, with its short wheelbase, tended to be twitchy and unpredictable. With only minimal time for Vandervell’s drivers to discern its vices before the 1949 British Grand Prix, it was a case of not if but when it would all go wrong. By mid-race distance, Raymond Mays had had enough of the recalcitrant vehicle and handed it over to BRM chief mechanic and development driver Ken Richardson. The car continued its capricious ways, spinning into the bystanders at Abbey Curve with fortunately neither driver nor onlookers suffering any significant injuries.

Peter Berthon, the chief engineer of BRM, had prepared the Thinwall Special for its first race. He penned a report which summed up his and Tony’s disenchantment with the car and its handling: too little power, too much weight, and much too unstable on fast bends. At least it gave Tony some hope. They had bought a Ferrari, and it was rubbish. If they couldn’t build a car better than this may as well give up now!

The terse missive to Enzo resulted in a compromise. Return the car to the Ferrari factory, and it would be exchanged with a more up to date model. Vandervell eventually obtained possession of a 2-stage supercharged 1.5 L engine…ensconced in the current long-wheelbase chassis. As a further conciliatory effort, Enzo also offered the services of Alberto Ascari to race the Thin Wall Special at the 1950 BRDC International Trophy.

During the race, an unhealthy sounding clamour emanating from the engine forced Ascari to abandon the contest before the waving of the chequered flag. When Vandervell stripped the engine down for post-race diagnosis and repairs, he was livid. It looked to be old and run down – a Ferrari reject rather than cutting edge Ferrari technology. The final affront was that it didn’t even contain his thin-wall bearings!

Alberto Ascari driving a Ferrari Thin Wall Special during the 1950 International Trophy Race at Silverstone Photo: Getty Images – Keystone/Stringer

The last thing Enzo wanted was a renamed and repainted Ferrari beating up his own progeny on the track, but he was also loath to get off-side one of his vital supply sources. Not only did Vandervell furnish Ferrari with his state of the art thin-wall bearings, but he also consulted on design features affecting the bearings and their lubrication. The ongoing negotiations balanced precariously. Tony complained…Enzo placated…Tony wheedled…Enzo promised…each doing their best to keep the other happy, but both still trying to seize the better part of the deal for themselves.

Tony eventually procured two different versions of the Ferrari 4.5 L normally aspirated engine. This was the power train with which Ferrari took Alfa Romeo down to the last race in 1951, only a smidgen of rubber causing them to come up short of the world championship spoils. As Thin Wall Specials…piloted by such celebrated names as Gonzales, Farina, Hawthorn and Collins…these would have enough non-championship wins to give Tony the incentive to continue in his quest as a constructor in his own right.

Giving every impression of being a rich man “playing” at motor racing, Tony did nothing to try to disabuse meddlesome inquirers of this opinion. As far as he was concerned, the less hype, the better. When the press attempted to dig for details, Tony would grumble, “We make bearings, not engines. Ferrari makes engines.” However, at the same time Vandervell was racing and tinkering with his Thin Wall Specials he was making plans…dreaming of building his own Formula One car.

A car was nothing without a power train. Norton began as a company the same year that Tony Vandervell was born…making “fittings and parts for two-wheeled trade”. Their first engine emerged in 1907. Tony already had connections to Norton. As well as racing them as a youngster, his father was appointed one of the original shareholders in 1913. Tony himself was a director until early in 1953 when his father sold the family shares, and Norton was taken over by Associated Motorcycles.

Problematically for Vandervell, Norton was still utilising a 1-cylinder engine. With a myriad of trophies adorning their cabinets and a dearth of ready funds adorning their bank accounts, there was little impetus to push engineering boundaries with ongoing research and development. Tony had a few more kilograms than Norton to propel across the tarmac. He would need more than one cylinder.

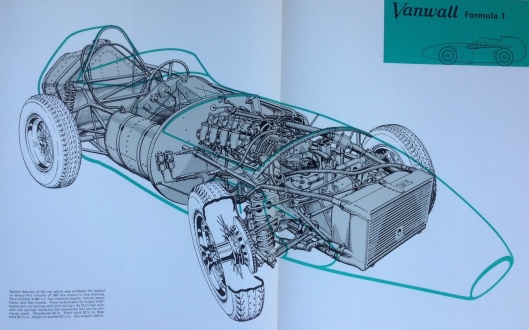

Vanwall VW5 – Photo by Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

Tony proposed that Norton development engineer Leo Kuzmicki fashion them a 4-cylinder engine out of four 1-cylinder engines. Kuzmicki knew that you couldn’t just take four 500 cc engines producing 50 hp, join them together, and make a 2-litre engine producing 200 hp. Engines were neither that simple nor that compliant. They were more akin to a dark art. Swish and swirl might be invisible, but their presence deep in the bowels of each cylinder could make the difference between success and failure. What looked plausible on paper wouldn’t necessarily perform when fashioned in cold and passionless aluminium and iron alloys.

Four cast-iron Norton cylinders were inserted into a Rolls Royce B40 crankcase – especially cast in aluminium alloy to keep the weight down. A Rolls Royce bottom-end may sound…posh…but, in reality, it was a crankcase developed for British Army vehicles. Its forerunner was built to embody the simple virtues of reliability, simplicity and economy…not usually the pedigree seen in the cutthroat world of motor racing. Surprisingly…it actually worked.

Drawing: James Allington

Next on the agenda was a sturdy metallic structure in which to place the freshly minted powertrain. Tony Vandervell and John Cooper were kindred spirits, Tony often ringing John on the weekend to discuss the finer points of machinery and racing. He asked Cooper for a frame in which to place his engine, along with a multitude of off the shelf Ferrari components. In exchange Tony offered John a supply of 500 cc Norton engines direct from the factory, to place in his Formula 3 entrants. This negated the need for Cooper to purchase a whole Norton motorcycle, just to procure its ensconced engine.

Owen Maddock designed the chassis, and 1954 was a learning year for Vanwall…step by step boring out the cylinders of their new engine, as well as discovering all the possible means for oil to make its escape from the essential paraphernalia of hoses and connections.

In September Vanwall headed off for their first reconnaissance visit to the land of the fast red cars. Power was essential at the Cathedral of Speed, but their single 2.5-litre engine had self-destructed on the test bed before the race. Despite this lack of capacity handicapping their ability to stretch their legs on the long straights, they managed to finish 7th – pitting to patch a broken oil pressure gauge along the way.

Handling of the Cooper chassis had seemed a bit erratic and arbitrary at Monza…but maybe it was just because their lack of power meant they were pushing the car to the extremes of its limit. At Pedralbes, this was no longer just a maybe. Peter Collins totalled the car during the first practice session, and two new chassis would be built for 1955. Just to be sure, Tony also bought a Maserati 250F…minus the engine of course. Maybe there was something to be learned from how the other breed of red cars was made.

The new Vanwall racing cars in the pits at Silverstone Racetrack before the start of the 1955 International Trophy race – Photo by Lee/Central Press/Getty Images

The planning of Vanwall’s foreign invasion continued into 1955, upgrading their equipment and fine-tuning their strategy. This time they had the full 2.5 litres of engine power with which to do battle, but they had already lost their star driver. Hawthorn had thrown in the towel in a fit of pique after multiple DNF’s and raced the last three races of the season for Ferrari. When both Vanwall’s failed to finish at Monza yet again, you couldn’t help but think that just maybe Hawthorn had made the right decision…though even Ferrari was struggling against the relentless might of Mercedes.

Harry Schell had won four local sprint races for Vanwall during 1955, but the faster the engine got, the more apparent the deficiencies of the chassis became. It was time to make a concerted effort to improve the configuration of the skeletal framework. Tony Vandervell willingly considered all propositions on lightening, stabilising, stiffening and simplifying the scaffolding lurking beneath the overlying metallic membrane.

They put bits on. They took other bits off. But the best suggestion came from one of their transport drivers. Derek Wootton was good friends with Colin Chapman, racing an Austin Seven special with him in their youth. Tony Vandervell had heard of Colin Chapman. Chapman had even written to him, inquiring about the possibility of using his 2-litre Vanwall engine in one of his sports cars. The Lotus Mark Vlll was Lotus’ first space frame chassis, weighing in at only 35 pounds. In July 1954 everyone noticed it when Chapman won with it at Silverstone, defeating Hans Herman’s Porsche.

Chapman was duly invited to the workshop to give them some much-needed advice. He tactfully started with suggesting possible alterations to the existing chassis. Eventually, he just said what he had thought from the very beginning. The whole thing was rubbish. It was useless to try to patch something that wasn’t working and never would work. They should just rebuild it from the beginning.

Then came the crucial question. Could Chapman build them a new chassis? Money was a meagre commodity at Lotus. Vanwall had no such shortage. It was a perfect exchange of superior engineering for ready cash. Chapman suggested that Frank Costin fashion the metallic covering…the latest in aerodynamic understanding and engineering. Costin calculated out his design on paper. If the numbers worked, then the car would be fast. It may not look like any other racing car at the track, but Costin was sure it would go faster.

The new car debuted at the BRDC International Trophy held at Silverstone on May 5, 1956. Although Vanwall couldn’t persuade Stirling Moss to sign with them for the 1956 season, they did wrangle him for their first race as Maserati wasn’t racing that weekend. Two Lancia-Ferrari D-50s were entered, but both retired with clutch problems. Moss won the 180-mile race, the engine running flawlessly. Breaking the lap record put the icing on the cake.

The remainder of the season left much to be desired, the only high point Harry Schell bringing the car home in fourth at the Belgium Grand Prix for their first Formula One points. With both cars failing to finish at Monza the year before, this time Tony increased his ammunition, and three cars were sent to fight it out with the locals. None of the Vanwall drivers saw the chequered flag.

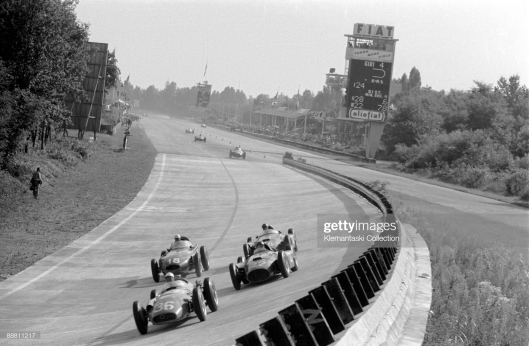

The 1956 Italian Grand Prix: Moss with the offset-engine Maserati 250F leads the Ferrari-Lancia D50s of Juan Manuel Fangio and Peter Collins while Harry Schell challenges in the Vanwall. Schell had to abandon his car out on the course with a fractured oil line, another victim of the merciless pounding from the rough banking. (Photo by Klemantaski Collection/Getty Images)

In 1957, Tony secured the driver he had been pursuing for years…Stirling Moss. Partnering him was two fellow Brits: Tony Brooks and Stuart Lewis-Evans. Vandervell was pleased. His British build car now had three top-notch British drivers. However, driver skill counted for nothing if the car couldn’t finish races. Finally, everything started to come together, so by the time Vanwall arrived in Northern Italy for their fourth campaign, they already had two wins credited to their name.

The sun beat down, the loudspeakers blared, and the mechanics shoved the cars onto their allotted places on the starting grid. The stage was set for the Blitzkrieg of Monza by the British. The dropping of the flag resulted in an instantaneous roar, as each driver fought fiercely for the lead position. Moss, from the middle of the front row, led into the first corner. By the end of the first lap Behra, his Maserati 250F getting a perfect start from the second row was behind him. Not letting the duo get away were Lewis-Evans, Brooks, and Fangio. It was three Vanwalls battling with two Maserati.

The five cars shortly had a significant gap on the remainder of the competitors, leaving the rest to fight it out for the single point spoils of sixth place. Then the cracks in the armour of the British bastion began to emerge. Tony Brooks and Stuart Lewis-Evans both pitted and then were forced to pit again…the engineers repairing stuck throttles, cracked cylinder heads, and even a missing gearbox bung. Both drivers lost multiple laps in the process. Eventually, Lewis-Evans was forced out of the race, but Tony Brooks would nurse his car through to finish in seventh place. He would also set the fastest lap…despite the major drawback of a poorly functioning clutch.

Sterling Moss being pushed to the grid at the 1957 Italian Grand Prix – Photo: Getty Images/Hulton Archive

By mid-race distance, Moss had pulled out a 17.5 second lead on Fangio. Behra was forced out on lap 49 with engine problems, and now it was only Moss versus Fangio. The Maserati couldn’t match the pace of the Vanwall, but Fangio was still hoping for mechanical difficulties to beset the last member of the usurpers of Italian pride. Fangio stopped on lap 44 for new rear tyres. He was now almost a lap down on Moss. Stirling wouldn’t stop until lap 77, ten laps from the end, for a quick splash and dash…a splash of oil and a dash of rubber on his right rear tyre.

Finishing almost a lap ahead of Fangio, the Tifosi crowding around Moss were as enthusiastic as if an Italian driving an Italian car had won the race. The Vanwall was enveloped by a British Flag. Moss was wrapped in the winner’s laurel wreath. The British anthem played. The victory Vanwall had sought for so long was finally theirs.

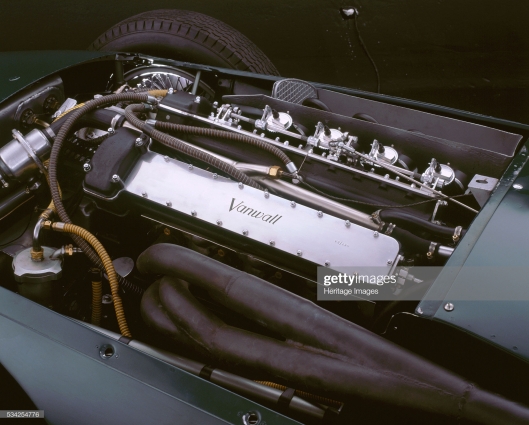

For the 1958 season the powers that be decided that racing needed to become more relevant to the everyday punter on the road…or maybe just more relevant to the pocketbooks of fuel company advertisers. Out went methanol based fuels and in came AvGas…still not what the everyday motorist used, but at least it was a step closer.

The change had critical repercussions on the Vanwall engine. Now in the fifth year of its development, it relied heavily on the cooling effects of methanol. Ferrari had an engine all ready to run on the new 100/130 AvGas. The Vanwall engine needed major modifications…spraying oil underneath each cylinder for cooling and reducing the pump stroke to keep the optimum air/fuel ratio.

1958 Vanwall 2.5 litre – Photo by National Motor Museum/Heritage Images/Getty Images

All this took time, and the engine still wasn’t ready by the beginning of the season. Argentina hosted the first race in the middle of January. Stirling Moss continued with Vanwall but kicked off his championship campaign by borrowing a Copper-Climax, managing to eke out his fuel and tyres to get to the end without stopping, beating Luigi Musso’s Ferrari by a smidge under three seconds. It was the first race victory for a rear-engine car, but at the time thought to be an aberration due more to strategy than outright speed.

In the end, it was close…very close…between Ferrari and Vanwall. The Vanwall was still very fast, but reliability remained its Achilles heel. Tony Brooks had three wins. They were the only races in which he would get points. Stirling Moss had four wins and one second place. Ferrari driver Mike Hawthorn had only one win but finished second five times. At Monza, Tony Brooks would take the laurels for Vanwall, Moss and Lewis-Evans both retiring with engine and gearbox issues.

The championship went down to the last race at Casablanca. Stirling Moss finished first, one place ahead of Mike Hawthorn, who was gifted second place by his new teammate Phil Hill. When the points for fastest lap were added up (three for Moss and five for Hawthorn), Moss was one point adrift of his fellow compatriot. For the fourth year in a row, Stirling Moss would finish runner-up in the championship.

It was enough to give Vanwall the first constructor’s championship…though if all ten race results had been counted – rather than just the top six for each marque – the two antagonists would fittingly have been tied on 57 points. Tony Vandervell then retired from Grand Prix racing, his health deteriorating rapidly, both physically with a failing heart and mentally after the death of Stuart Lewis-Evans six days after his accident at Casablanca.

Denis Jenkinson and Cyril Posthumus wrote in their book on Vanwall that, “It was the “chief’s” racing team and they were all proud to be part of it, working with ultimate victory in view as much as Vandervell did. He himself always made the point that his cars were the result of a team effort, no one person being singled out for praise. From the number-one driver to the boy who swept up the workshop, all were essential members of the team, and the ever-present Tony Vandervell imbued a strong feeling of solidarity and devotion to the great cause.”

“Working together in common cause,

to produce the miraculous.”

~Working Together – David Whyte~

Juan Manuel Fangio, Tony Brooks, Stirling Moss, Stuart Lewis-Evans, Maserati 250F, Vanwall VW 5, Grand Prix of Italy, Monza, 8 September 1957. Photo by Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

References:

Lead Photo: LAT Images

Vanwall – The Story of Tony Vandervell and His Racing Cars: Denis Jenkinson and Cyril Posthumus

Classic Racing Engines: Karl Ludvigsen

Lotus – The Early Years: Peter Ross

An Intensely Interesting R.A.C. BRITISH GRAND PRIX: Motorsport Magazine – https://www.motorsportmagazine.com/archive/article/june-1949/19/intensely-interesting-rac-british-grand-prix\

XXV Gran Premio Pescara – A Real Grand Prix Victory for Vanwall https://www.motorsportmagazine.com/archive/article/september-1957/16/xxv-gran-premio-pescara

XXVIII Gran Premio d’Italia: A TRULY WONDERFUL VANWALL VICTORY – https://www.motorsportmagazine.com/archive/article/october-1957/29/xxviii-gran-premio-ditalia

The Cars of Frank Costin – https://www.motorsportmagazine.com/archive/article/september-1984/35/cars-frank-costin

Video: Monza 1957 Italy gp formula 1 by magistar – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ka6VJKN5krk

The 1958 Formula 1 Season with Raymond Baxter – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8uM3yB5-LEM